There are some artworks that feel too alive to be still. David Altmejd’s sculptures don’t just sit in a gallery they pulse, twist, and quietly haunt you. With every glance, you see something new: a fragment of bone hidden behind crystal, a face that seems to shift when you’re not looking, limbs stretching into forms you can’t quite explain. His pieces don’t just challenge the boundaries of sculpture they dissolve them.

Altmejd’s world is one where biology collides with fantasy, where movement is frozen in the act of becoming. His humanoid figures and mutant hybrids look as though they’ve been caught mid-mutation part creature, part spirit, part beautiful nightmare. There’s a rhythm to his work that’s hard to ignore, a disturbing harmony between decay and growth, horror and elegance. You’re not just observing his art — you’re being pulled into it.

If you’ve ever felt the eerie pull of an image you shouldn’t keep staring at like in our 20 Creepy Pictures That’ll Chill You to the Bone you’ll recognize that same energy in Altmejd’s work. It’s not gore or shock value. It’s the slow, inescapable hypnotism of something that feels too close to real.

Some viewers describe his sculptures as grotesque. Others call them magical. But no one walks away unmoved. And that’s the strange genius of David Altmejd: he makes discomfort beautiful. You might flinch. You might stare. But one thing is certain you won’t be able to look away.

-

1 Half Human, Half Dream — All Unsettling

This isn’t just a sculpture it’s a face unraveling, rebuilding, and mutating all at once. Altmejd’s use of synthetic materials, real hair, pastel tones, and anatomical surrealism pulls you into a kind of psychological limbo. It's part portrait, part explosion — a physical manifestation of transformation, memory, and something deeper that doesn’t quite speak in words. Look closer, and it feels like you’ve interrupted a being in the middle of evolving into something else entirely. This is what Altmejd does best: he makes change visible, beautiful, and quietly terrifying.

-

Advertisement

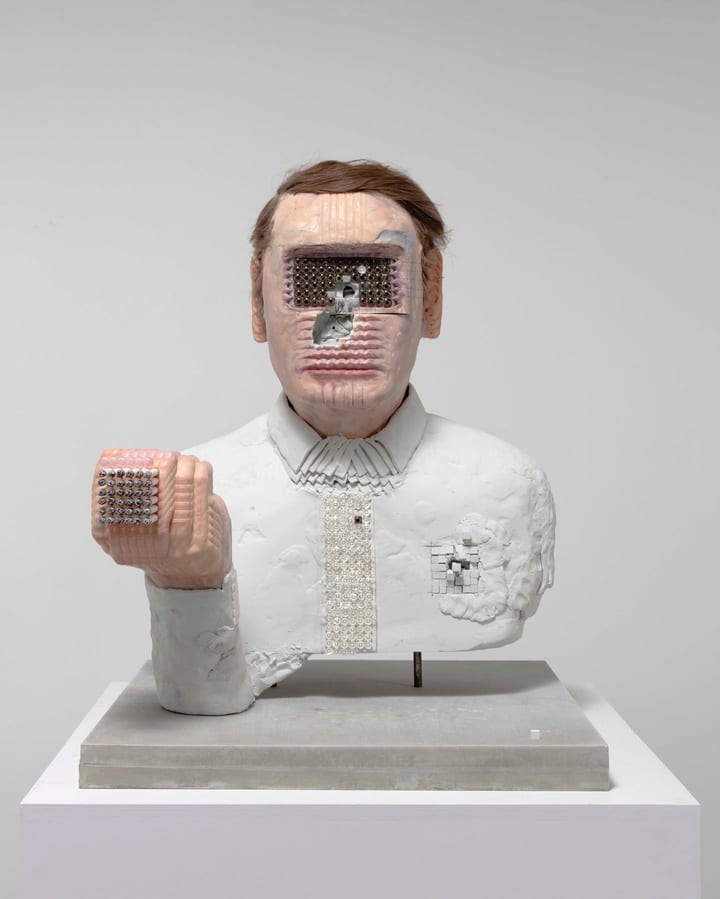

2 The Architect of Disintegration

This piece doesn’t just challenge how we see the human form — it deconstructs the very act of perception itself. In typical David Altmejd fashion, the bust seems both monumental and fragile. A crisp white shirt suggests formality, control, maybe even identity. But the face? It's a digital glitch turned to flesh. A surface peeled back and reassembled with blocks, mirrors, and crystal-like modules that reflect not just light — but uncertainty.

The symmetry is eerie. One hand clenches a cube, mimicking the embedded structures within the face — as if thought and creation are looping back into each other. The “eye” is a fragmented chamber, turning the act of seeing into something architectural, almost mechanical. But beneath that logic is something broken. Human. Missing.

You get the feeling this figure is not decaying, but transforming — mid-thought, mid-self, mid-story. Like Altmejd's other sculptures, it's not just meant to be looked at. It feels like it’s processing you back. Every angle is a question. Every material — skin, metal, plaster, crystal — is a contradiction. Cold but alive. Elegant but wrong.

This isn’t just art. It’s a confrontation: between self and machine, beauty and distortion, wholeness and unraveling.

-

3 Thinking Through the Skull

There is something deeply unsettling — yet quietly poetic — about this figure. With her impossibly large, exposed skull and contemplative posture, she feels more like a vessel than a person. The surface of her head is not smooth but marked, cracked, and imprinted with a faint deer-like symbol, as if evolution left notes behind. Her hand, half-painted and strangely delicate, rests near her temple — not in pain, but in focus. As if she's listening to something no one else can hear.

This is one of Altmejd’s quietest pieces, yet it might be his most psychologically invasive. It doesn’t scream transformation the way others do. It suggests internal evolution — a mutation of thought. Her body is stitched with geometric patterns, and strands of human hair flow through her otherwise alien frame. The juxtaposition is deliberate. She is part machine, part mythology, part memory — caught somewhere between organic intelligence and synthetic divinity.

You don’t know if she’s broken or becoming. But you do feel her loneliness. And that, perhaps, is the most human part of her. In Altmejd’s world, the mind is not hidden inside the body — it grows around it, and sometimes far beyond it.

-

Advertisement

4 The Anatomy of a Spell

This sculpture is not simply a portrait — it’s an incantation cast in flesh, wire, and plaster. From the side, you notice a man’s profile: beard, bruised tones, a thoughtful hand poised mid-gesture. But then your eyes are pulled to the green spine of beads jutting from his nose — precise, ritualistic, unnatural. It’s a spell, a growth, a message. Something too deliberate to be random, yet too strange to explain.

The figure’s body is a chaotic blend of sculpted stone and collapse — a mass that looks carved by erosion and impulse, as if half of it has already begun to dissolve. His ears are exaggerated, strangely tender, jutting out from a disfigured skull that looks half-finished, half-rewritten. One foot is fused into a crystal-like base, the other simply gone. The word “RA” scrawled at the sculpture’s base could be mythic, childish, divine — or all three.

This is David Altmejd’s vocabulary at its most cryptic: bodily collapse, organic geometry, and subconscious symbolism all tangled together. The more you try to decode it, the more you realize it’s meant to be felt — not solved. This isn’t a man. This is a ritual with skin.

-

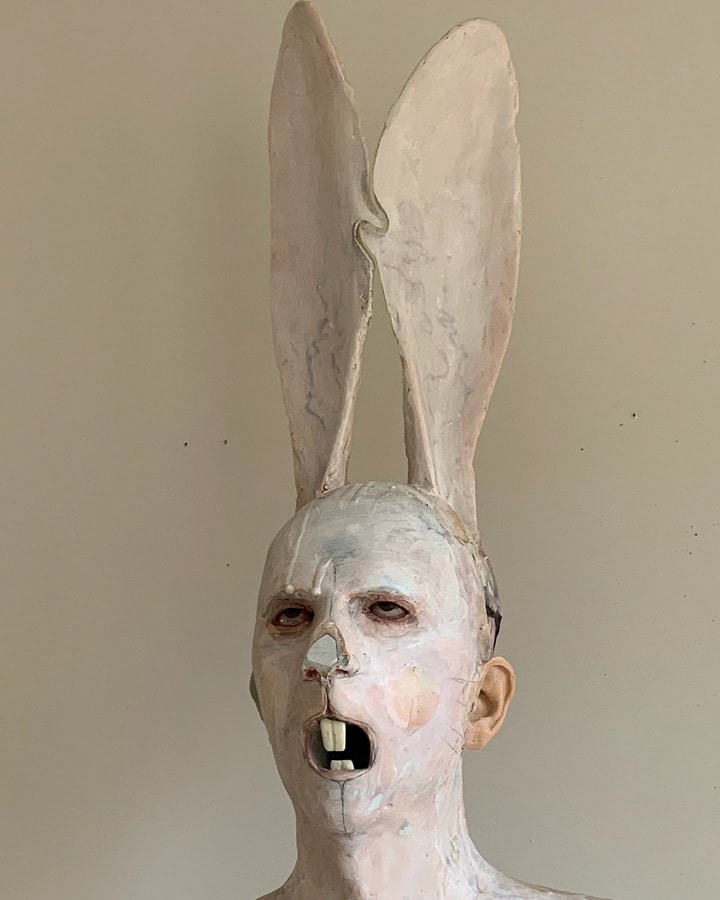

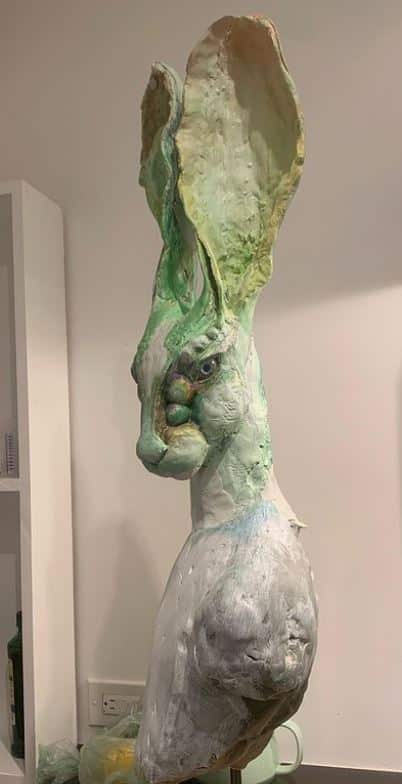

5 The Rabbit Mask Screamed First

This is not a costume. It’s a confrontation.

With towering ears, exaggerated rodent teeth, and a frozen open mouth that feels somewhere between scream and silence, this figure doesn’t hide behind the rabbit — it becomes it. Altmejd’s choice here isn’t playful or whimsical. It’s disturbing. Visceral. And oddly human. The pale pastel skin is cracked and uneven, the surface weathered like something trying to shed its own shape. The cheeks are blushed like a doll’s — but there’s nothing innocent about this face.

There’s a tension in this piece that never lets go. It speaks to the horror of transformation, the grotesque nature of blending identities. The figure feels mid-process — caught between predator and prey, human and animal, truth and mask. Those tall ears don’t suggest listening. They suggest alertness. Panic. Survival. The mouth gapes open, but we don’t hear a sound. We feel it.

Altmejd often explores the body as a site of disruption, and this piece is no different. It’s about what happens when symbols we once trusted (a bunny, a costume, a blush) are pushed too far. This isn’t a dreamlike fantasy. It’s a fever dream dressed in fur and skin, daring us to look away — and knowing we won’t.

-

Advertisement

6 The Music That Mutated the Machine

This is no musician. This is an evolution wearing music as armor.

At first glance, it looks playful — a futuristic figure mid-guitar solo, lost in the act of creation. But linger a little longer, and you realize the “guitar” is fused into the body. The strings are bone. The frets are wires. This is not performance. It’s transformation. Altmejd’s figure is neither alien nor human — but a collapsed hybrid of both, sculpted with such surreal precision it feels like an artifact from a future that hasn’t happened yet.

The face is partially hidden by an insectoid visor. The skin, sculpted in smooth, anatomical curves, wraps around a posture that’s oddly devotional — like the creature isn’t playing music… it’s channeling something. The instrument has wings, but not for flight. They anchor it, stretch it open like a relic in mid-bloom. You begin to wonder: is this how language survives when the body fails? Through shape? Through sound?

Altmejd’s work often pushes the boundary between body and environment, but this piece suggests a new kind of interface — not between man and machine, but between instinct and creation. The sculpture doesn’t play music. It is music — broken into form, paused just long enough for you to witness it.

-

7 He Was Already Splitting When He Looked Back

This sculpture doesn’t scream. It stares — and stares again. And again.

At first, you see a man. Wounded, vulnerable, quietly sculpted with long hair and tired eyes. But then you notice the distortion: multiple faces fused together in a slow, painful bloom. Altmejd doesn’t just sculpt a person — he sculpts the moment they fracture. The face is caught in motion, in mutation, like a memory replaying in layers that no longer align. Each eye seems to look in a different direction, as if no single perspective is enough to hold the truth.

The figure holds a bowl in one hand and stirring sticks in the other — a ritual gesture. Calm. Almost domestic. But the face says otherwise. It’s the juxtaposition that unnerves you. A person trying to carry on the most human of acts while their identity disassembles in real time.

There’s no blood, no horror, and yet the disquiet is visceral. You can feel the weight of memory, of time collapsing into the skin. It’s a portrait of someone trying to remain whole while being pulled apart by something unseen — grief, thought, the past.

And just when you think you’ve studied it enough, a new eye catches yours. A new face forms. And you realize: this sculpture isn’t finished. It’s still becoming.

-

Advertisement

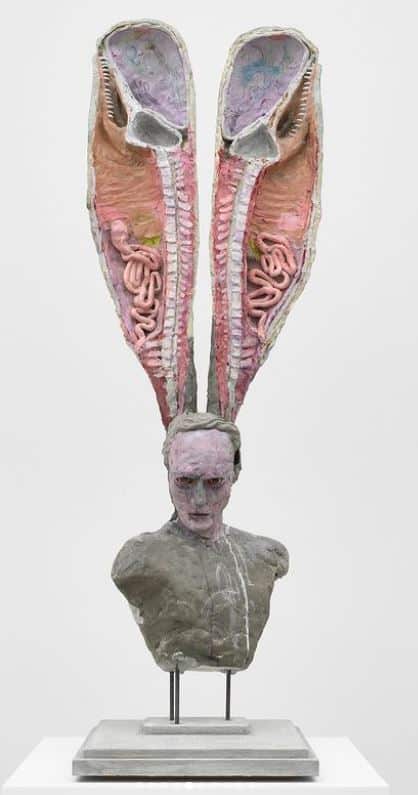

8 The Ears Were Never Meant to Hear

There is something grotesquely surgical about this piece — not just because of the exposed intestines curled into two enormous upright ears, but because of how calm the face beneath them remains. The figure itself is near-expressionless, almost classical in its stillness, while above him rise these impossibly tall, sliced-open forms, both anatomical and symbolic. It’s not simply shocking. It’s biological theatre. It’s absurdity rendered with too much detail to dismiss.

Altmejd often works with contradictions — beauty and horror, elegance and mutation — and this is one of his boldest expressions of that balance. These ears don’t listen. They expose. They reveal the vulnerable machinery of the body as though Altmejd is screaming: What you think is simple is not. The human form, in his hands, is a site of transformation, transparency, and ritual dissection.

It’s easy to think of this piece as surreal. But it’s more than that. It’s anatomical vulnerability made sacred. The ears become wings. The intestines become language. The stillness of the bust becomes more disturbing than any expression of pain.

You’re not just looking at a figure. You’re witnessing a body trying to become more — by turning itself inside out.

-

9 Memory, Eroded in Profile

This isn’t a head. It’s a collapse. A landscape of thoughts frozen mid-crumble. In this profile view, what was once a face has been carved and layered into a fragmented ruin. The beard remains intact. The ear is untouched. But everything around it—bone, skull, brain—is dissolving into something you can’t name. It’s no longer portraiture. It’s a biography in ruins.

The outer edge of the head curls into itself like geological strata, revealing deep, hollow caverns that once held form. The forehead has burst open, spilling cloudlike material over cracked resin. Patches of hair stubbornly cling to the scalp. Paint and synthetic skin bleed together across the surface. What you're seeing isn't decomposition — it's disassembly. Not death, but undoing.

Altmejd’s sculptures often reflect mutation, but this one is pure erosion of self. The interior has become exterior. Thought has become matter. The self, exposed, isn’t heroic — it’s fragile, layered, and always falling apart in ways we try to hold together.

And yet, the posture remains upright. There’s dignity in the disintegration. As if it knows we’re watching, and it doesn’t mind. Because if anything survives, it’s the act of being seen.

-

Advertisement

10 The Mask Wasn’t for Hiding

This is one of Altmejd’s quietest pieces — and one of his most revealing. A fragmented bust of a man holds a flat white disc, like a mask, but not in front of his face. Instead, he presents it outward, calmly, as if offering it back to the viewer. The face itself is a ruined palette: gouged, punctured, painted over with scattered patches of pigment and puncture. Like a surface that’s been tried on by a hundred selves and left unfinished.

His eyes remain intact — but they're surrounded by visual noise. There’s no symmetry, no resolution. Just an expression that refuses to explain itself. The mask in his hand doesn’t match his features. It’s too smooth, too clean. You realize it’s not a disguise — it’s a contradiction. One face for the world. Another that’s always breaking underneath.

Altmejd’s work often explores identity in collapse, but this piece is deeply personal. It feels like a self-portrait torn through the lens of memory and anxiety. The blankness of the mask is louder than any scream. It's what we all try to hold up when everything else begins to fracture.

This sculpture doesn’t beg to be understood. It asks only that you admit: you’ve worn that mask too.

-

11 The Hole Where Knowing Used to Be

This sculpture is not violent. It’s quiet. And that’s what makes it terrifying.

A severed head, pale and strangely preserved, stares forward — but where the eyes should be, there is nothing. Just one massive cavity, punched straight through the face. Not a wound, but a void. And yet the edges glisten with crystal. The absence is not emptiness — it’s geology. Like the face has eroded into something ancient, or perhaps something sacred.

Altmejd has always explored what happens when identity begins to fail, when the self unravels into symbol. This is one of his starkest expressions. The hole is precise, rounded, impossible. It’s as if consciousness itself has been tunneled out and replaced by the raw material of time. There's no scream. No resistance. Just submission to the fact that something essential is missing — and it’s beautiful in its absence.

This head doesn’t ask to be understood. It asks to be felt. And what you feel is silence. Not peace. Not horror. Just the heavy stillness of what remains after memory has left. It’s not death. It’s what’s left of a person when identity dissolves — and all that's left is structure, surface, and stone.

-

Advertisement

12 The Guardian at the Edge of Reason

This isn’t a rabbit. This is a sentinel.

Altmejd has long played with hybrid forms — human, animal, spirit — but here, he leans fully into myth. The figure towers upright, chest proud, ears impossibly long. From the side, it radiates strength. But look closer, and you’ll see something more unsettling: its posture is too still. Its gaze too direct. This creature isn’t posing. It’s watching.

The surface is cracked, bruised, streaked with green and white — as if it has emerged from deep within some overgrown forest, half-painted by time and weather. Its body is humanoid, muscular, vulnerable. But its face? It’s mask-like. Or maybe not a mask at all. Maybe this is its true face, and everything else is the costume.

There’s a strange sacredness here — like this sculpture guards a doorway between reality and whatever Altmejd is pulling us toward. It’s not grotesque. It’s not violent. But it’s deeply wrong in a way that whispers, Don’t turn your back on it.

As with so many of his pieces, the horror here isn’t loud. It’s slow. Lingering. Like a dream that waits to disturb you long after you’ve woken up.

-

13 Something Broke, But It Kept Smoking

This sculpture doesn’t ask for attention — it already has it. A solitary head, hovering above a thin support rod, gazes forward with remarkable calm. Its face is young, nearly classical in symmetry — until you notice the rupture. A gouged wound runs through the forehead, a jagged tunnel opened between skin and void. Flesh peeled away. Form exposed.

And yet, just below, a detached hand gently holds a cigarette — elegant, unfazed, almost bored. It’s this contradiction that makes the piece so unforgettable. There’s damage here. Something traumatic. And the response is detachment. Style. Poise.

Altmejd’s sculptures often explore collapse, but this one leans into apathy. It isn’t grief. It isn’t pain. It’s that strange space between: where the self is still performing while everything behind the face is crumbling. The head is fractured, but the hand is composed. It reminds you of those moments when we say we’re fine — even when something deep inside us has already split open.

This is a portrait of post-trauma elegance. A sculpture that doesn’t scream but simply exhales. The horror is casual. The damage is real. But the cigarette still burns.

-

Advertisement

14 The Beast Who Knew Love

This sculpture is both myth and wound.

A creature — part human, part beast — sits in a meditative pose, frozen mid-stillness. Its surface is a mosaic of contradiction: animal hair, glass shards, crystal veins, golden spheres, and a rose pierced directly into the flesh of its thigh. There is no one story here. There are hundreds — layered, broken, recomposed. You don’t know if the figure is healing or unraveling. You only know that it’s trying.

A white hand touches its shoulder from behind — soft, almost maternal. A second hand clutches a black patch over the heart. A third stretches toward the rose, as if reaching through the pain for beauty. Embedded faces appear where they shouldn’t — one in the chest, one near the groin. They’re not decoration. They’re ghosts. Memories. Parts of this creature that once were separate, now fused into something new and raw and almost holy.

Altmejd’s work often explores transformation, but here he offers vulnerability. This isn’t about horror or mutation. This is about the cost of becoming something more. Something fractured, but not destroyed.

The beast is not terrifying. It’s tender. It’s waiting. And somehow, it knows love — even if it had to be torn apart to feel it.

-

15 What Remains After the Mask Melts

This sculpture doesn’t depict a face. It shows what’s left of one after time, trauma, and identity have all taken their turn.

Altmejd’s figure is partly skull, partly wax, partly animal — a head seemingly frozen mid-mutation. The nose is smeared into flesh-colored folds. The lips are slurred into wax. The eyes, eerily intact, stare through the ruins of the face with an expression that’s not fear — it’s recognition. This head knows exactly what it has become.

Hair spills unevenly from both sides like a memory that won’t let go. Plastic, pigment, and resin melt together like a scream that’s been softened by time. There’s no clean line between decay and transformation here — and that’s the point. Altmejd doesn’t just sculpt faces. He sculpts processes — the slow, silent erosion of self when no one’s looking.

This figure feels both intimate and monstrous. It’s not a creature. It’s someone. Maybe even you. A mirror held too long. A self you don’t recognize until it’s too late. And somehow, in all this visual chaos, you feel sadness more than horror. A soft grief for what used to be human, before it turned into everything else.

-

Advertisement

16 The Head That Grew a Garden

It lies there, face tilted to the sky, as if it once belonged to something that could stand tall — before it became part of the earth. At first glance, it’s simply unsettling: a sculpted head torn open, the skull hollowed and sparkling with crystalized matter. But the more you stare, the more it feels… peaceful.

This isn’t a decapitation. It’s a burial.

Altmejd has always explored transformation through flesh and fracture — but here, the setting changes the story. This head isn’t in a gallery. It’s in the grass, under sun, facing a wall of greenery like it’s finally resting. The violence of the missing scalp gives way to something strangely beautiful. The wound becomes a mineral bloom. The brain becomes stone. The decay becomes a seedbed.

This sculpture asks you to consider where identity goes when it's no longer held together by bone and skin. It suggests that memory is porous. That selfhood is a process. That perhaps, even after collapse, beauty can emerge — not despite the damage, but because of it.

Here, the monstrous becomes organic. The grotesque becomes grounded. And for the first time, the head does not watch us.

It returns to the dirt. And becomes something else entirely.

-

17 The Professional Who Couldn't Hold It In

At first glance, the sculpture feels composed. A professional. Hair tightly knotted. Crisp white collar. The expression is calm, even poised — the kind of face you'd pass on the street or see across a meeting table. But something is wrong. Something is erupting from inside. A soft, distorted hand has begun to push through the top of the skull, bulging out of the forehead like a subconscious rebellion.

This is Altmejd at his most psychologically precise — the tension between what we present and what we suppress. The face says “everything is fine.” The anatomy says otherwise.

From behind the bun, a cavity forms — hollow, dark, unsettling. A whisper of internal rot beneath outward control. The color is pale, almost waxy. But the lighting gives it life. It’s not a corpse. It’s a mask. And that hand? It isn’t reaching out. It’s emerging. Not for help — but to speak.

Altmejd’s work often exposes what we hide: the chaos under elegance, the surreal beneath structure. And this piece is a monument to that internal break — the one you try to contain until it breaks through the surface and demands to be seen.

Still haunted? You should be.

Altmejd’s work lives in that fragile space between beauty and breakdown — and once you’ve seen it, it doesn’t let go. His sculptures don’t just disturb your eyes. They lodge in your thoughts, long after the page is closed.

But if this kind of eerie energy speaks to you, don’t stop here.

Dive even deeper into the darkness with The Scariest Monsters from Myth and Legend That Will Haunt Your Dreams. From ancient beasts to whispered folklore, these creatures have terrified generations — and some of them feel eerily close to what Altmejd might sculpt next.

Dive even deeper into the darkness with

Dive even deeper into the darkness with

0 Comments